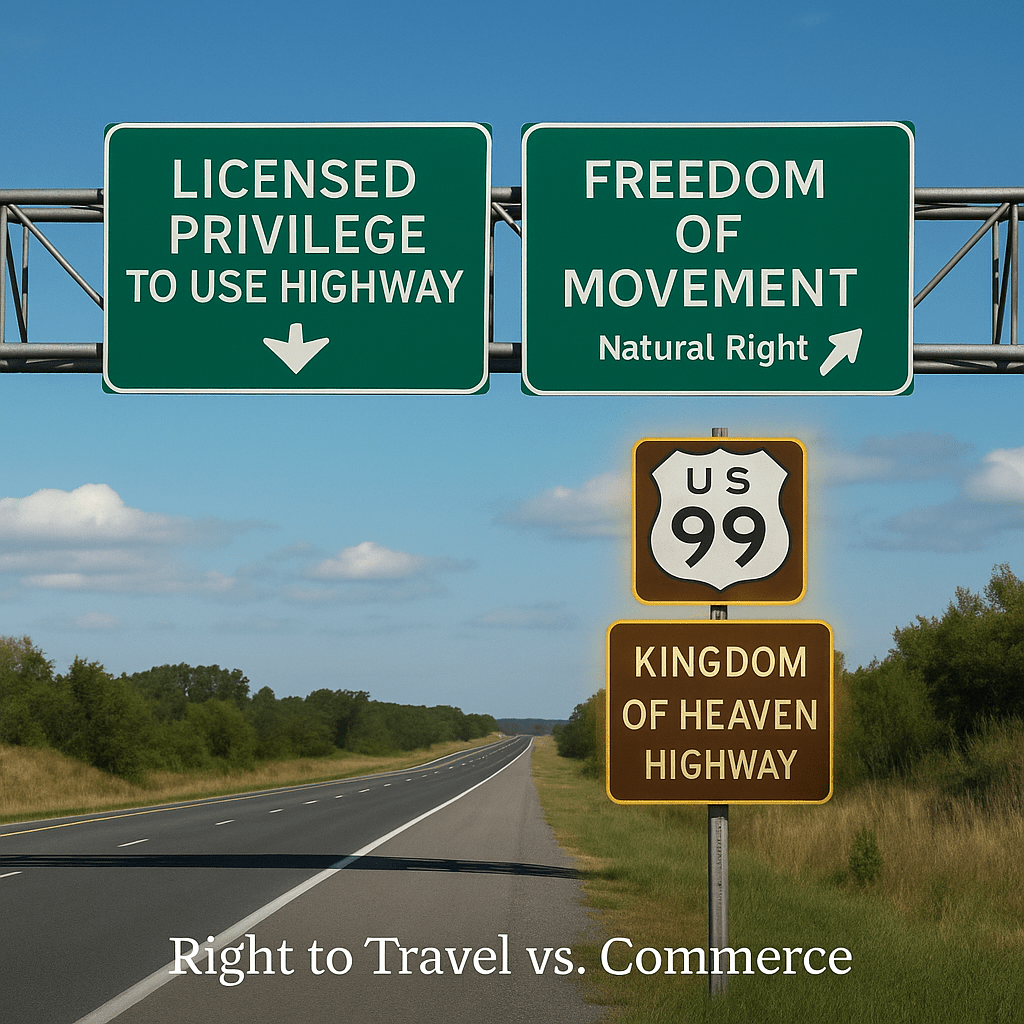

The distinction between the right to use public highways for ordinary travel and the licensed privilege to use the same roads for commerce hits home for us. Freedom of movement is part of our birthright. This isn’t abstract: we are still seeking remedy in Okanogan County District Court after a 2022 traffic stop, and our county tort claim was recently denied—hence our resolve to check what the law actually says. Across the last century, many state courts recognized that ordinary, non-commercial travel on public roads belongs to the people, whereas using those roads as a place of business can be licensed or denied. A recent Facebook summary by Allen Paul collects those cases and invites a fresh look. This article presents the highlights and pairs them with the U.S. Supreme Court’s treatment of the right to travel and state motor-vehicle regulation, so readers can separate enduring principles from over-broad claims.

Link to Facebook post: stpedrnoSoai05h 5t:d79l41ate3itcghY0ygslmehmhicr8l0h1ci 91a6 ·

Allen Paul said, “Many older state decisions (including Thompson v. Smith) articulate the familiar distinction: private, non-commercial travel on public highways is a common right, whereas using highways for hire/commerce is a special privilege that the state may license or deny. I list several controlling state cases below and provide citations.

The U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly recognized a constitutional “right to travel” (e.g., Kent v. Dulles, Shapiro v. Thompson, United States v. Guest), but the Supreme Court has not held that driver-licensing statutes are limited to commercial users only. In fact, the Court has allowed states broad police-power regulation of motor vehicles (e.g., Hendrick v. Maryland). I give the key Supreme Court authorities next and note their relationship to the “license-only-for-commerce” claim.

Below are the cases and short annotations with sources (I emphasize the most load-bearing authorities with citations). If you want, I can format these into a memo or provide block quotations from the opinions.

State cases (supporting the private-travel vs commercial-use distinction)

1. Thompson v. Smith, 155 Va. 367, 154 S.E. 579 (Va. 1930) — classic Virginia decision stating the citizen’s right to travel on public highways for ordinary personal use is a “common right,” while the state may regulate/ license commercial uses; court struck down an ordinance authorizing an official to revoke a private permit without standards.

2. State ex rel. Schafer v. City of Spokane (often cited as State v. City of Spokane), 109 Wash. 360, 186 P. 864 (Wash. 1920) — discusses the difference between ordinary travel (a common right) and use of highways as a place of business (a privilege that may be regulated).

3. Willis v. Buck, 81 Mont. 472, 263 P. 982 (Mont. 1927/28) — upholds legislation regulating carriers and explains that using the highway “as a place of business for private gain” is a privilege and not a vested right.

4. Chicago Motor Coach Co. v. City of Chicago, 337 Ill. 200, 169 N.E. 22 (Ill. 1929) — Illinois decision enjoining a municipal ordinance that attempted to prohibit motor-bus operations; important for the distinction between private travel and municipal regulation of commercial carriers. (Often cited in discussions about when municipalities may regulate commercial vehicles.)

5. Additional state authorities (collected summaries): treatises and compilations list many similar decisions (e.g., State v. Johnson, Cummins v. Homes, Barney v. Board of Railroad Commissioners, etc.) that reiterate the “private travel vs. commerce” distinction. See the compiled travel citations.

U.S. Supreme Court cases (on the right to travel and state regulation)

1. Kent v. Dulles, 357 U.S. 116 (1958) — recognizes the right to travel (here, international travel/passport denial) as part of the liberty protected by the Due Process Clause. This is a leading right-to-travel decision. Important: Kent recognizes the constitutional liberty to travel but is about passports and denial of international travel — not a holding that driver licensing is limited to commerce.

2. Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969) — holds that durational residency requirements for welfare burden the right to interstate travel; again, establishes travel as a fundamental right for constitutional review. It does not say driver licensing is only for commercial users.

3. United States v. Guest, 383 U.S. 745 (1966) — discusses constitutional protection of interstate travel from interference (civil-rights context). Useful for showing the constitutional protection around travel as a civil right.

4. Hendrick v. Maryland, 235 U.S. 610 (1915) — upholds state authority to require vehicle registration and license fees; demonstrates the Supreme Court’s recognition of state police power to regulate motor vehicles for safety and commerce-related concerns. This case is frequently cited to show that states can constitutionally require registrations/licenses for motor vehicles. This is the key Supreme Court case that undercuts any categorical “licenses only for commerce” rule.

5. Other Supreme Court treatment and commentary on the right to travel appear across many decisions and briefs; the Court applies heightened review when state action burdens interstate movement but has not invalidated routine licensing/registration schemes for drivers acting in noncommercial contexts. See collected right-to-travel materials.

How to use these authorities in argument (practical notes)

If your point is: “There is an older, well-established line of state cases recognizing a common-law right to travel and distinguishing private travel from commercial use,” you can cite Thompson v. Smith and the Washington, Montana, Illinois decisions above — those are directly on point.

If your point is: “Therefore driver-licensing statutes are valid only as to commercial drivers,” be cautious: the U.S. Supreme Court has permitted states to require licenses/registration for motor vehicles (e.g., Hendrick), and later federal decisions recognize travel as a fundamental liberty but do not categorically exempt ordinary driving from state licensing/regulation. In short — state courts often drew the private/commerce distinction; the Supreme Court has recognized travel as fundamental but also sustained licensing/registration under state police powers.

here’s the table of authorities ;

It lists the key state and U.S. Supreme Court cases recognizing the distinction between private travel (a right) and commercial use of highways (a regulable privilege), along with short holdings

—

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES — RIGHT TO TRAVEL vs. COMMERCIAL USE

Case Court / Year Citation Core Holding / Quotation

Thompson v. Smith Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia (1930) 155 Va. 367, 154 S.E. 579, 71 A.L.R. 604 “The right of a citizen to travel upon the public highways and to transport his property thereon… is not a mere privilege… but a common right.” The state may regulate traffic, but it “cannot arbitrarily deprive” citizens of this right.

State ex rel. Schafer v. City of Spokane Supreme Court of Washington (1920) 109 Wash. 360, 186 P. 864 The court held that “The right of a citizen to travel upon the highway and transport his property thereon, in the ordinary course of life and business, differs radically from that of one who makes the highway his place of business.”

Willis v. Buck Supreme Court of Montana (1927) 81 Mont. 472, 263 P. 982 Recognized that using public highways “as a place of business for private gain” is a privilege subject to regulation, while “the ordinary right of travel” belongs to all citizens.

Chicago Motor Coach Co. v. City of Chicago Supreme Court of Illinois (1929) 337 Ill. 200, 169 N.E. 22 “The use of the highway for the purpose of gain is special and extraordinary, and may be prohibited or regulated by the legislature.” Ordinary personal travel is a right, not a special privilege.

Hadfield v. Lundin Supreme Court of Washington (1924) 98 Wash. 657, 168 P. 516 “The right of the citizen to travel upon the public highway and to transport his property thereon in the ordinary course of life and business… is a common right.” Commercial carriage for hire is a privilege.

Teche Lines v. Danforth Supreme Court of Mississippi (1937) 12 So. 2d 784 The court reaffirmed that “a distinction must be observed between the right of a citizen to travel upon the highways and the use of the highways for hire or commercial gain.”

Kent v. Dulles U.S. Supreme Court (1958) 357 U.S. 116 Recognized the “right to travel” as part of the liberty protected under the Fifth Amendment: “The right to travel is part of the ‘liberty’ of which the citizen cannot be deprived without due process of law.”

Shapiro v. Thompson U.S. Supreme Court (1969) 394 U.S. 618 Affirmed that freedom to travel between states is a fundamental right protected by the Constitution.

United States v. Guest U.S. Supreme Court (1966) 383 U.S. 745 Recognized the right of interstate travel as a fundamental constitutional right whose obstruction may be federally punished.

Hendrick v. Maryland U.S. Supreme Court (1915) 235 U.S. 610 Upheld state power to require registration and licensing of motor vehicles for safety purposes. The Court acknowledged that while travel is a right, the state may regulate its incidents for safety and order.

—

Summary of Principle

1. The Common-Law Rule (State Cases)

Across multiple states—Virginia, Washington, Illinois, Montana, and Mississippi—courts consistently recognized:

> “The ordinary use of highways for personal travel is a common right, protected by liberty; but use of highways as a business or for profit is a privilege that the State may regulate or license.”

2. The Federal Rule (U.S. Supreme Court)

The Supreme Court has affirmed the right to travel as a fundamental liberty, but has simultaneously upheld reasonable regulation of vehicles under state police powers (Hendrick v. Maryland). Thus, while the constitutional right to travel exists, the method of travel (motor vehicle operation) may still be regulated for safety.”

__________________________________

Dean Phillips said, “Allen Paul I believe it was a judge by name of Brandeis (so?) who spoke about the most comprehensive of all rights, the right to be let alone.”

Yes—you’re thinking of Justice Louis D. Brandeis.

The quote is from his dissent in Olmstead v. United States, 277 U.S. 438, 478 (1928):

“the right to be let alone—the most comprehensive of rights and the right most valued by civilized men.” Legal Information Institute+1

Context: Brandeis argued that government wiretapping without judicial safeguards is an unjustifiable intrusion on privacy protected by the Fourth Amendment. Legal Information Institute

Background note: decades earlier, Warren & Brandeis’s 1890 Harvard Law Review article coined the privacy ideal as the “right to be let alone,” which Brandeis later echoed from the bench.

And Furious-Qodannin Black said, “I hear you but you’re way behind on this bro if you’re still talking about this here…

But I’m not trying to clown whatsoever I’m proud!

Some of us have been on this mission for 10 years plus and have given up many automobiles to the thieves.

The problem is not your right to travel! The true attack or counterattack is the problem of the lack of due process before they’re making their moves regarding your driver’s license the whole issue behind licensing who is in control ultimately of the licensing system and what is it for why was it instigated?

Most people act like these things were just God sent.”

_________________________________________

Nothing here is legal advice; it’s a curated research guide so readers can verify claims directly in the opinions.

Leave a comment